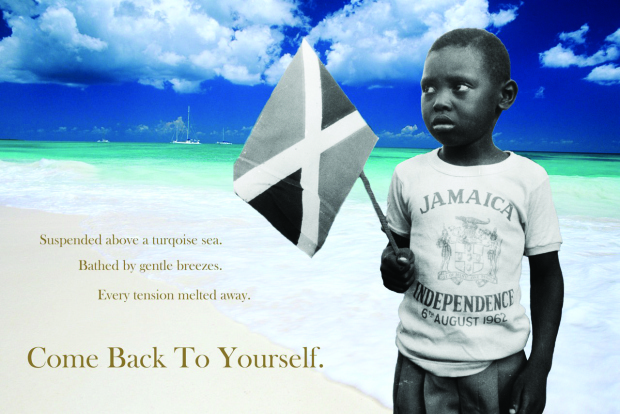

(Art by Andrea Chung)

Only the fittest will survive. This Darwinian statement was the only thing I remembered from high school biology class, which was held in a room that had fetuses of different developmental stage—(“unwanted bastard children”, one friend jokingly called them)—floating in large jars of vinegar inside glass shelves in the back of the classroom. I remember looking at those jars—at the refracted light, the dust motes dancing in the sun rays coming in from the glass windows of the old Victorian building, the grainy reflection of myself, barely eleven years old—and thinking I would never make it. Not here. In this jar. Not in Jamaica.

I knew instinctively that if I were to graduate and live in my country, I would wither faster than the rose bushes choked by the vines of Running Mary’s outside my classroom. Back then I had developed anxiety that condensed in sweaty palms that I often rubbed in the front part of my uniform skirt. It probably looked like I was continuously pressing my pleats as if the iron and starch hadn’t done their share of the work. It was especially embarrassing in dance classes where the teacher—a woman who use to beat us with a wooden stick if we lacked coordination—would attempt to adjust my flexed or pointed toes and find them moist; or when I would slip on the polished floors because my feet produced its very own puddle. I also had knots in my stomach every morning that teas and crackers made worse; and took lots of deep breaths, for I would always feel like I was drowning. These spells were like vapors, appearing then disappearing, though often.

I would come to find out that such anxiety was a part of being raised in a British common-wealth country. The rules, the regulations, the staunch expectation of propriety, respectability, excellence. You were made to feel like you were competing for something; made to feel like you would never be good enough. I was beaten by teachers at my primary school who thought eighty-five percent wasn’t good enough on a test; beaten whenever I was late; beaten if I wore the wrong earrings; beaten if I misspelled a word; beaten if I got an equation wrong (hence my lifelong hatred for Math); beaten if I dared let our dialect—Jamaican Patois—slip from my mouth; beaten if I had my hair braided—a style deemed too African for the British ideal. One time I was exempted from beatings for a whole month because my father visited from America and slipped my teacher a hundred US dollars.

Sometimes I thought primary school children were just beaten for the black of our skin, for our working class status, and for our broad features that some of us had come to hate, wishing they were straight and fine and light like that of the invisible people in Britain dictating to us how to wear our hair and our uniforms with not a rumple in sight; and even how to stand and walk—as erect as the Buckingham Palace guards. The headmistress of my primary school, a Chinese woman by the name of Sister Shirley Chung, made us stand in the sun for hours after devotion as a form of punishment. To her, we were a group of rowdy black children deserving of such torture. In high school I had begun to imagine—after viewing an award ceremony at Jamaica House where a government official was getting knighted by the Queen—that Jamaicans were like the Queen’s horses, gritting our teeth, jumping over hurdles, and galloping over hills and across valleys, trampling each other for her approval—that British Honor of distinction and excellence.

Excellence was a word I’d come to hate, though innately I strove for it, subjecting my mind and body to torture reminiscent of the beatings I used to get. There were times, for example, when I refused to eat until assignments were complete; times when I ripped out pages or deleted works that hadn’t gotten approval from others. Deep inside, the ten year old girl was holding on to the fear of not being good enough; the fear of being lashed, if not with a switch, then with failure. In high school I was never awarded any certificates of excellence—an award given to exceptional students at my high school every November. I wasn’t tapped to be a part of School Challenge Quiz or things like that, which was the pride and joy of Jamaican children bent on being the perfect examples the elders wanted them to be. Pressured them to be. I was an average student who never really sought leadership roles. The thought of Head Girl for the whole school was too reminiscent of Uncle Toms on a plantation. I just wanted to get by and get out.

The one thing I had going for me was my writing. I wrote for comfort. The words flowed as easily as my breathing that eventually slowed the calmer I became. I wrote in exercise books and hid them. There was something liberating in dictating the direction of a story, the fate of a character. I felt like God—though not the judgmental and prejudiced god from my understanding back then, based on the acts committed by people like Sister Shirley or my dance teacher who abused us in his name. I was more inclined to mercy, because mercy was what I wanted, needed for myself. I didn’t know this then, but when I read my journals that my mother now keeps on her bookshelves as though they are published novels, I see them for what they were—elaborate fantasies of salvation.

Unlike most writers, English was not my favorite subject. Not while living in Jamaica. In a country where true excellence is evaluated with practical subjects like Math and Science, English, like Art, was a guilty pleasure if taken seriously. It’s only use was to learn the tools to speak and write well—especially the latter since Jamaicans are expected to be ambassadors of our country wherever we go. God forbid we open our mouths elsewhere and Jamaican Patois spew out like vomit. For that reason, patois has always been forbidden in schools. However, since language is a huge part of culture, such regulation limits the speaker. Moreover, I was never assigned books by Jamaican authors. To this day I cannot tell you who the influential Jamaican writers were at that time. I was reading Shakespeare, some of which I can still recite in my sleep, and dissecting themes in novels such as SHANE, TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, CATCHER IN THE RYE, and a random book about a swamp and a lighthouse. It was no surprise then that my characters were all white with no hint of our dialect when I first started writing stories. When I did attempt to write something true to my experience in a personal statement for my college application, I was told by my English teacher who also doubled as a college advisor that my writing would not get me anywhere. “It won’t get you through the door. Write something more relevant.” She said, handing me back my essay with red ink all over it, and slamming that proverbial door in my face. Of all the times I had been beaten in primary school for the sake of improvement so that I could be an exemplary citizen and student, I never cried. Not until that day when the one thing I found solace in was wrenched out of my hands and mangled with red ink.

I put down my pen and focused on the sciences. I wanted to defy those who never thought excellence could come out of the working class by getting into a good university. “But neither of your parents went to college,” I was told by the man in charge of helping Jamaican students apply for colleges overseas. “Your parents’ education determine where you’ll end up. And Cornell?” He laughed. “That’s not for you.”

I was as alone and lost as those floating fetuses—the unwanted bastard children—inside the jars in the biology lab. My mother had a habit of encouraging me to watch Profile with Ian Boyne and by pasting newspaper clippings around the house of successful doctors, business people, engineers, and lawyers who had gone off to England to study, returning to Jamaica as successful professionals—the epitome of excellence. I felt pressured to make my family proud. I never told them about the beatings in primary school or that I was discouraged to apply to the college I wanted to get into because of them. That year I pushed hard academically but was still not awarded a certificate of excellence. It wasn’t the work itself that was hard, it was the competitive, classist environment that was stifling.

The lure of America began with a chill. I had gotten so overwhelmed that I took sick. It was then that I learned that there’s such a thing as psychosomatic illness. My mother, desperate for answers, called my father and asked if he could do something. And he did. I moved to America to live with him. I could finally breathe properly, no longer having to take deep breaths to submerge myself under immense pressure. I was given time to acclimate to my new environment, before applying to the one school I wanted to get into. I submitted the same essay I was told wouldn’t get me through the door and was accepted early. Someone must have liked it. Furthermore, someone must have not cared that my parents didn’t go to college. I encountered more acceptance of my work there than when I was back home. Ironically, Cornell University is known for its competitiveness and suicides due to the high standards set in place for its students; and yet, it was there that I thrived—on that hill surrounded by gray clouds with no sun.

One may argue that being a student in Jamaica with its demand for excellence and high standards had prepared me for my new environment; but I ended up losing a lot by erasing the bad memories. Grace Jones said it best in her memoir when she wrote, “Once I left Jamaica I had to wash all [the bad memories] away, brainwashing myself in a way…that viciousness took Jamaica away with it.” I lived in exile for a while—a coping mechanism. It took many years to rid myself of the insecurities I developed being raised in a country that made me feel unwelcome, undervalued. When I finally came into myself as a writer, I found freedom in expressing myself. My priorities finally shifted. No longer did I pledge allegiance to my country, but to the stories that I was called to write. The sad part is I had to leave Jamaica to be reborn.

Nicole Dennis-Benn